Shuzo Takiguchi and Yukio Nakagawa April 10 Thursday - April 30 Wednesday, 2025

At Gallery NOW, from Thursday, April 10 to Wednesday, April 30, 2025, poet, artist, and art critic Shuzo Takiguchi (from Toyama Prefecture from 1903 to 1979) and Ikebana artist Yukio Nakagawa (from 1918 to 2012 from Kagawa Prefecture We will hold an exhibition of myself.

Shuzo Takiguchi formed the “Experimental Workshop” with Toru Takemitsu and others in 1951, and left pioneering achievements in the post-war avant-garde art movement.

Around the same time, Takemiya Gallery was opened in Kanda, Tokyo, and Takiguchi was entrusted with the selection of people who would provide the venue free of charge to young newcomers. Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Eiku, Atsushi Kawahara, Yayoi Kusama, Yoshishige Saito, Tatsuoki Nambada, Keiji Nomiyama, Bushiro Mouri, Kazuo Yagi, etc. presented and held 208 exhibitions by 1957.

In 1958, he went to Europe as the representative judge of the Venice Biennale, met with André Breton, Salvador Dali, Marcel Duchamp, etc., and introduced and embodyed the philosophy of surrealism in Japan.

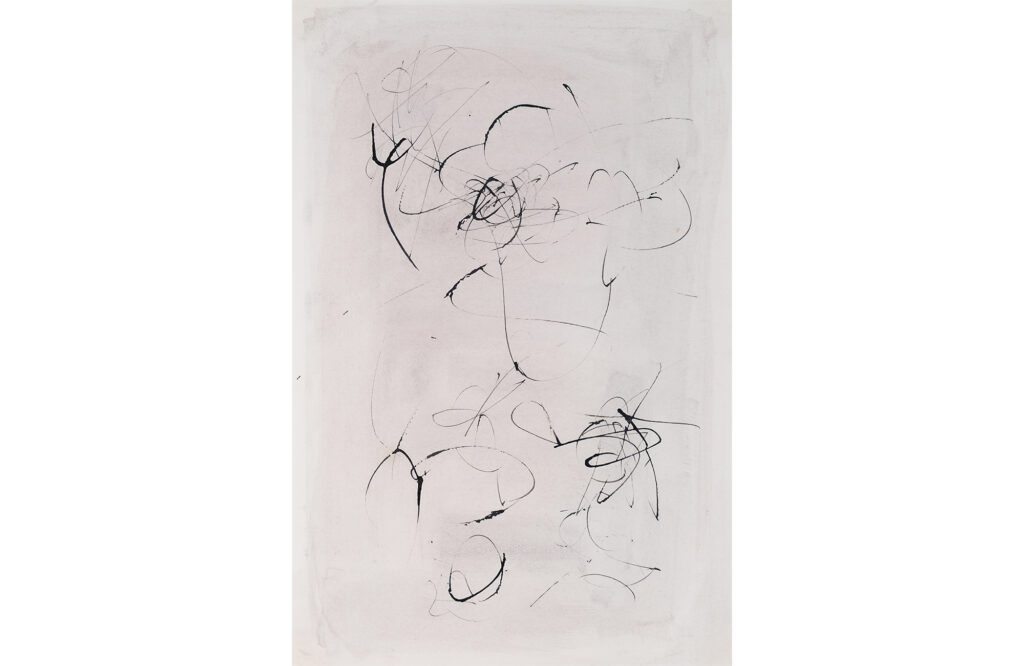

Since 1960, he has been in full swing, and his first solo exhibition “From My Painting” was held at the Minami Tenko Gallery. After that, he left many works as an artist.

In addition, he took on as a special lawyer in the thousand yen bill trial of Akasegawarahira (1965-1970).

Takiguchi’s Decarcomany’s works were exhibited along with Dali and Milo at the Surrealism Exhibition at the Pompidou Center, the National Museum of Modern Art, which was held since September 2024.

It was a commemorative exhibition 100 years after Andre Breton made a declaration of surrealism.

On the other hand, Yukio Nakagawa moved from Marugame City to Tokyo in 1956 at the age of 38, and did not belong to the school and did not take disciples, and lived modestly in coffee shops and clubs, making his own expression into the “art of life”.

The “Anger Leaf”, which can be said to have declared de-shaping produced in 1969, was born from these, and after that, Nakagawa has successively created works that shake the traditional concept of Ikebana, such as “Hanabozu”, “Izumi” and “Mayama”.

It can be said that the encounter with Shuzo Takiguchi sublimated Nakagawa’s Ikebana, who spent his life, into flapping his wings in the field of art.

Here are some of Takiguchi’s contributions to “Hana and Yukio Nakagawa’s Works”.

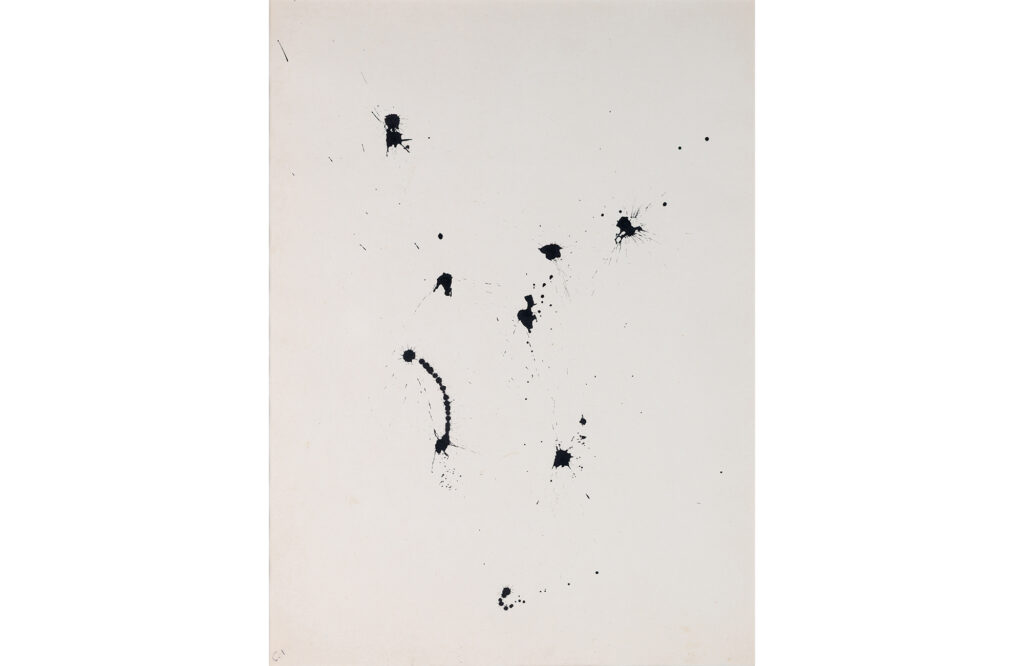

One evening, Yukio Nakagawa visited my study and showed me a strange event on the table. While waiting for a self-made glass jar filled with only carnation flowers, probably hundreds, upside down on white Japanese paper, the flower liquid that oozed out quietly began to draw a trajectory on the paper. ( Abbreviated) On-site verification of the paradox that flowers can be done. And even the quiet disintegration of the stone-like stereotype of Ikebana can be seen. Probably, Ikebana’s self-analysis was happening.

Shuzo Takiguchi (from the contribution to Kyoka Siansho “Hana Yukio Nakagawa’s Works”)

Nakagawa’s expression gradually became larger, and in the 2000 tribute Takiguchi Shuzo “Hanka Olive”, the olive tree was brought into the gallery space in a state of uprooting and the venue was buried. ( There is an olive tree in the garden of the Takiguchi family, and the fruit is said to have been bottled and distributed to close people)

After that, in 2002, “Tenku Sanka” was held on the Shinano Riverbed at the pre-event of the “Earth Art Festival Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale”. Kazuo Ohno, a dancer, danced under the petals of 1 million tulip petals falling from the helicopter.

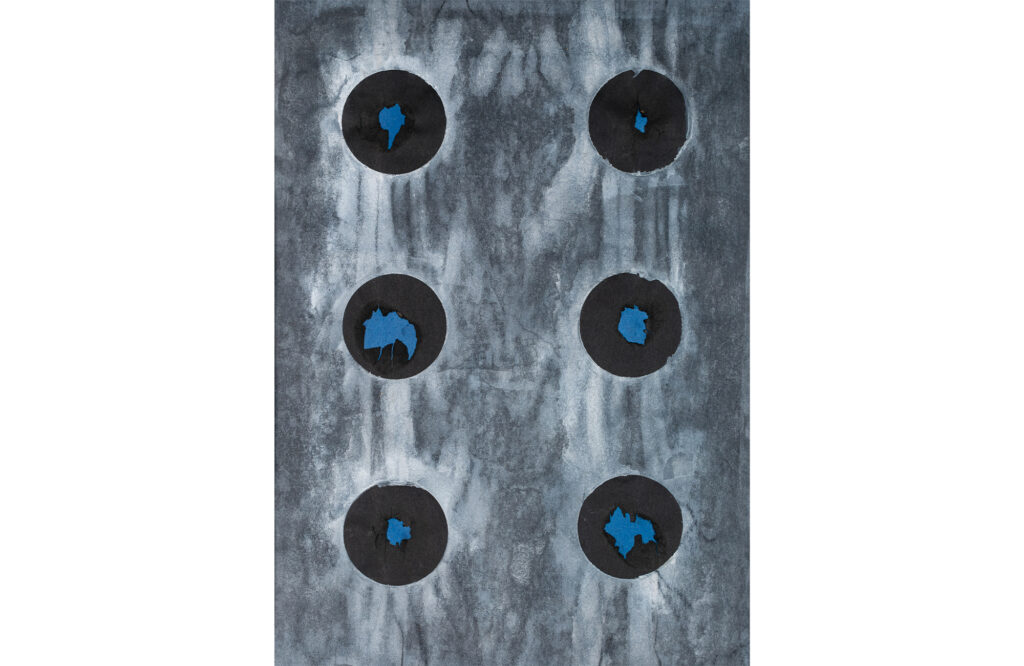

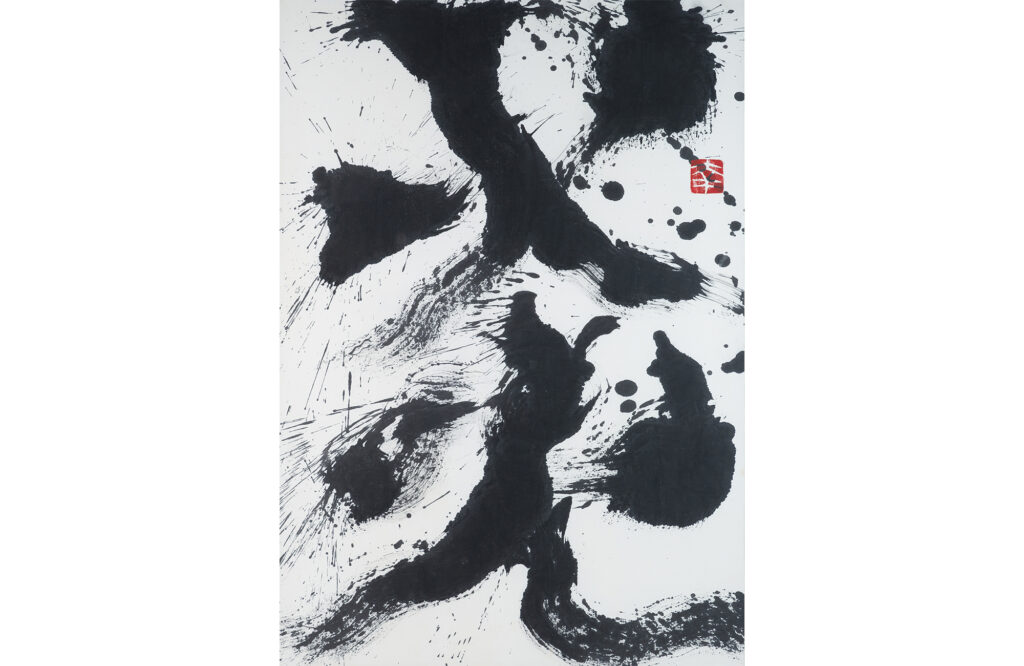

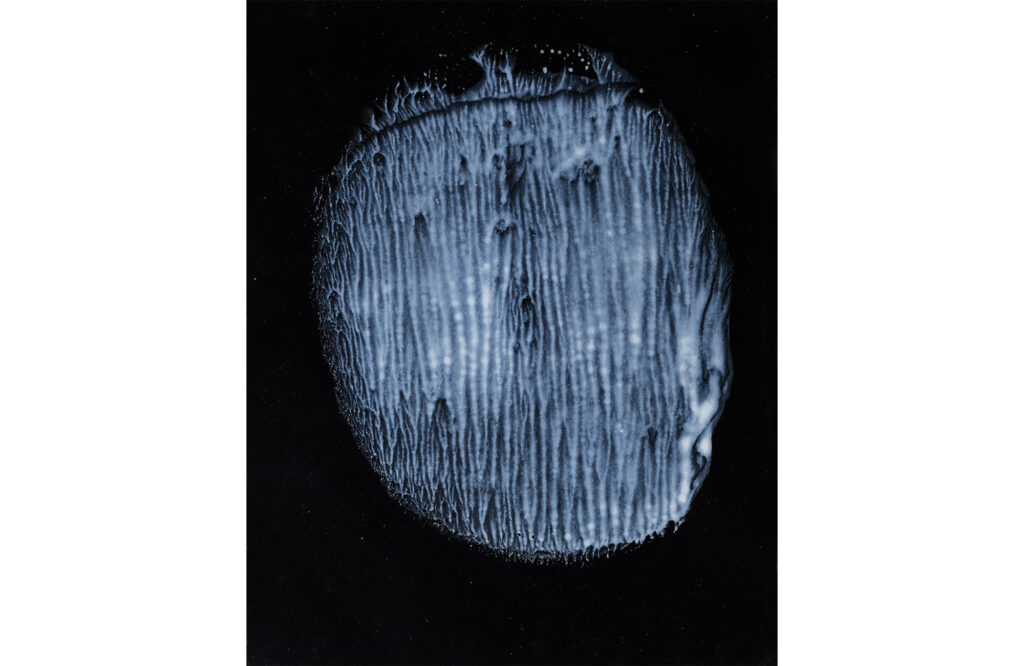

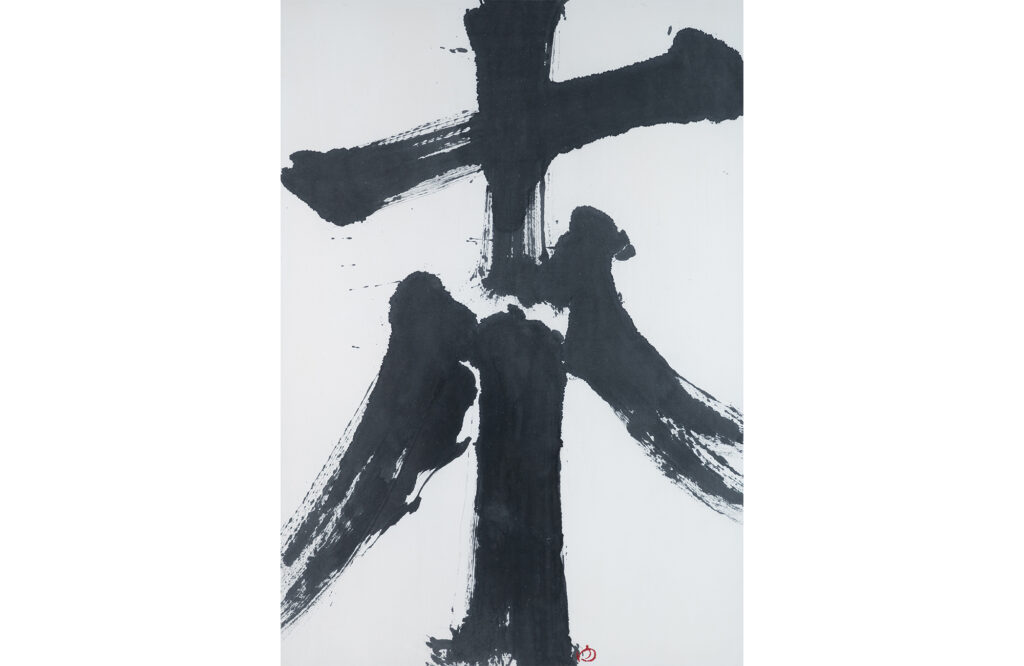

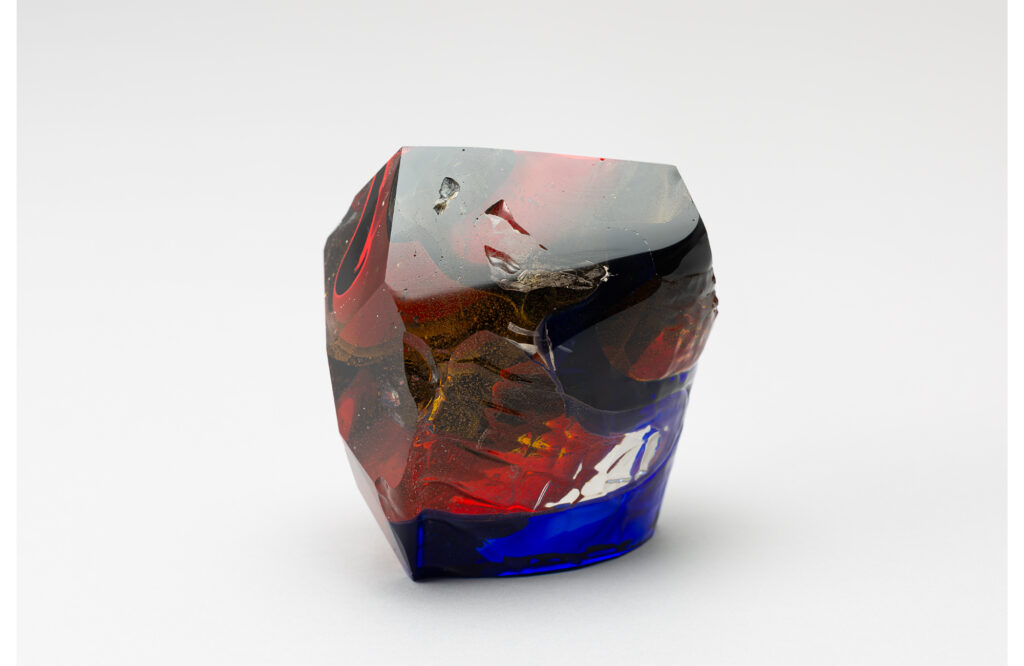

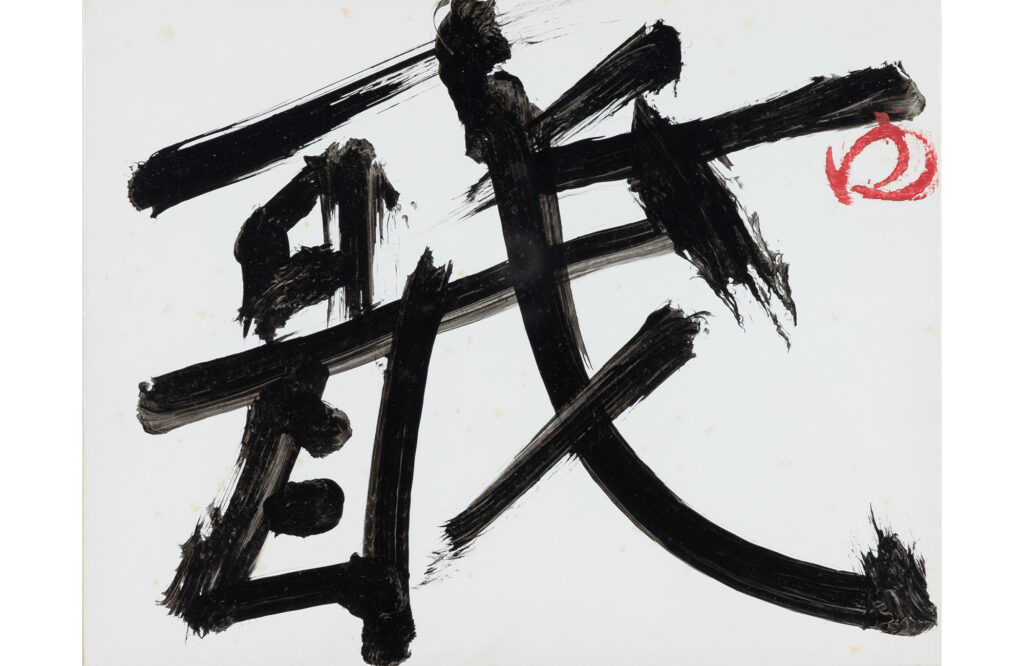

In this exhibition, Takiguchi’s drawing, decalcomany of transcribed paintings, and burnt drawing with burnt kogashi and watercolors. Photographic works such as “Kyu Hiraku” and “Ma no Yama” made with tulips from Nakagawa’s Toyama, flower music, calligraphy, and self-made glass drawn by extracting flower juice will be exhibited.

It would be great if you could work on experimental events that lead to Takiguchi and Nakagawa, and draw on the spirit of challenge that has been increased to your own art.

Period: April 10, 2025 (Thursday) – April 30 (Wednesday)

Opening hours: 10:00 – 17:00

Closed days: Sundays and Mondays

Shuzo Takiguchi and Yukio Nakagawa: Flowers of Memory

——Carnations, olives, tulips——

On the first day of the exhibition commemorating the publication of “Hana: Works of Yukio Nakagawa” (1977), a telegram arrived at the Kinokuniya Gallery, the venue for the exhibition.

The telegram read, “Tonariya he denpo wo utsume de tasayo hananoi no chiitsuinisugata no kosu kokoro kara orokobi mo shiagemasu.”

The sender is the poet and art critic Shuzo Takiguchi. He is the well-known author of “Kyoka Shikansho,” a moving essay contributed to this collection. Nakagawa, who lived in Ekoda, Nakano Ward, where Philosopher’s Park is located, visited the Takiguchi residence in Nishi-Ochiai, Shinjuku Ward from time to time, and kept a notebook detailing the works and conversations he had with the artist. Nakagawa’s first solo exhibition in Tokyo (1968), it is noted that he appeared at the venue on the first day of the exhibition.

However, Takiguchi himself was unable to go out due to a cerebral thrombosis and herniated disc, and was in no condition to travel to Shinjuku on March 17, the opening day of the exhibition. Even if the telegram was a substitute for the opening of the exhibition, the fact that the artist was able to leave such an intimate call for help now makes one feel irresistible.

Although this was a commemorative exhibition, it was not an exhibition of the 60 photographs included in “Hana,” but rather an objet d’art made of layers of Japanese paper lying at the entrance, and a giant rubber balloon filled with water, “Don’t touch me,” on the floor. On the other hand, “Where to,” in which about 30 dead lotus leaves sway with the movement of a person at the end of a brass wire, occupies a corner of the exhibition hall. Takiguchi delighted Nakagawa by being able to visit this place on the 20th.

Flower Liquid Running Carnation

Kyoka Shikansho” was written in 1972. The text states that the impetus for this work came from seeing “a kind of bizarre event,” the prototype for the carnation “Hanabozu” (1973), which Nakagawa had performed at the Takiguchi residence late the previous year. Nakagawa packed the sealed, red, bleeding petals in a homemade glass vessel and placed them upside down on a sheet of washi paper. Takiguchi called this event a solemn “ceremony” and presented Nakagawa with a book, postcards, and olives on New Year’s Day. Such exchanges occurred frequently.

However, as far as the author is aware, Takiguchi has not written a single article on Nakagawa or ikebana since then.

In his afterword to “Kyoka and Objects” (first published in 1938) and “Ikebana and Formative Arts” (first published in 1957), which he reprinted in the magazine Sogetsu (1875) after his “Hanabozu” experience, Takiguchi wrote, “I can only blush when I read them again. He published several articles (1953-1966) on Sofu Teshigahara, the founder of the Sogetsu school, and pointed out that while Western objects are an attempt to make things speak in their own words, “ikebana objects are trying to go the opposite way,” giving the impression that he took an ambivalent attitude of both expecting and questioning Sofu’s work. Sofu was ambivalent in his attitude, expressing both expectations and doubts.

Both of them can be read in “Collection Shuzo Takiguchi” Vol. 10, “Design Theory: Tradition and Creation” (1991), which was published after his death.

We assume that Nakagawa saw in Hanabozu the “quiet dissolution of the stony stereotype of ikebana,” and thought that Nakagawa created flowers that were “crazy flowers” but not “objects. His final brushstrokes seem to indicate that it was Nakagawa’s ikebana that forced him to reconsider his own view of objects.

If we were to mention only two people who were important to Nakagawa, the first was Mirei Shigemori, a landscape architect and founder of “Ikebana Geijutsu,” whom he met for the first time in 1955. Mirei, known for his checkered garden at Tofukuji Temple, was an idealist of abstract art, and according to his son Hiromitsu, he “had no understanding” of surrealism or art objects. Shigemori, however, was probably the one who nurtured Nakagawa to become a connoisseur of Japanese arts and crafts in general, including calligraphy, crafts, and gardens. Calligraphy and glass production provided Nakagawa with the resources to create works of art after he had broken with the schools.

After much contemplation of surrealism and objects, Takiguchi sealed off his hopes for object flowers. Nakagawa’s reverence for both artists remained unchanged throughout his life, and he could be said to be their guardian deity. If so, what position did Nakagawa occupy for Takiguchi?

Olive Root

In a 1963 entry in his autograph annals, Takiguchi confessed that he felt “a deep contradiction in the labor of writing as a profession. However, even after his 60th birthday, he continued to send letters, even in the form of personal letters, to individual artists and exhibitions. The recipients seem to encompass all of the quality adventurers of postwar art, and one gets a sense of the poet’s penetrating eye and the extent of his influence.

After his death, “Shuzo Takiguchi: Dream Drift Objects” (Setagaya Art Museum, 2005) was held, with about 700 works by 130 artists, including some of his own. Although there were several glass works by Nakagawa, they did not stand out in particular. Meanwhile, the “Hommage Shuzo Takiguchi” (1981-2007) exhibition, organized by the Satani Gallery, continued for the 28th time. The organizers, Satani Gallery and Shiseido, appointed Nakagawa for this commemorative 20th exhibition of homages to acquaintances of Takiguchi, including his poetry collection “The Gaze of Matter,” Experimental Studio, Joan Miró, A. Breton, and Tetsuro Komai, and prepared The Ginza Art Space at Shiseido as the venue. Among Takiguchi’s many acquaintances, Nakagawa seemed to have a special significance.

Nakagawa uprooted four olive trees and restored them to life in the basement of Ginza. Although the story of the Takiguchi mansion’s olive trees has been told repeatedly, no one has ever seen the roots that spread their tentacles deep underground. Even Takiguchi did not know that the olives were uprooted. The olives, which arrived in Okayama by boat from Teshima, Shodoshima, and then by truck overland, are from the Seto Inland Sea, the birthplace of Nakagawa, and in the distant past were dedicated to Zeus, Athens, and Apollo, symbolizing immortality and fruitfulness. During the exhibition, not only did the olives not wither even though their leaves fell little by little, but new shoots peeked out, much to the delight of Nakagawa, who visited the exhibition hall on a daily basis.

In the last year of the 20th century, the exhibition was the last project to be held in the space that was scheduled to be closed, and because of Takiguchi’s love of olives, the exhibition attracted a great deal of attention and set a record for the number of visitors to the venue. One of the many responses to the exhibition was an essay by the author, “‘Olive,’ ‘Ark,’ and ‘Uninterrupted Rest’ Revived as Signs of Friendship among the Avant-Garde” (“Asahi Graph” July 21, 2000).

The title of the exhibition, “Flower Offering Olive,” must have been named by the organizers after a passage in Kyoka Shikansho, which says, “In the beginning, ikebana was also ‘flower offering’ and ‘flower dedication.

Tulips in Toyama and Niigata

As is well known, Nakagawa makes unique choices in both floral materials and vessels. For example, manjushage, rubber tubing, and Chinese cabbage. As a result, his works are both animal-like and mineral-like, and he has created unique works that have never existed in the 600-year history of ikebana, such as his use of rotting flowers and pouring flower juice into his works. Still, to name a few of his favorite flower materials and works other than his masterpieces, we can list: apples = “Statue of Delicious,” roses = “Flowers Know,” lotus = “Flower Madness” and “Sky,” carnations = “Angry Leaves” and “Holy Book,” and tulips = “Devil’s Mountain” and “Tulip Alien. …….

Nakagawa’s revelation of the “art of life” came in 1980, and his entire oeuvre could be called the “art of life. Takiguchi had extorted it when he telegraphed, “The life of a flower finally leaves a figure.” And Takiguchi, a native of Toyama, may have secretly named the “expounding Hiraku” with Tonami tulips that decorates the latter part of his collection “Hana” as packing art or mail art.

Nakagawa’s most talked-about event was the “Flower Offering Olive. Then there was the miraculous “Sky Scattering” (2002), in which Butoh dancer Kazuo Ohno was invited to scatter 200,000 tulips from Jomon no Sato, or perhaps a million petals, from a helicopter down on the Shinano Riverbed.

Yukio Nakagawa, who visualized and created the creation of heaven and earth through the medium of flowers, is still ubiquitous on both the other shore and this shore.

Akiko Moriyama

Akiko Moriyama

Born in Niigata Prefecture in 1953, Akiko MORIYAMA graduated from the Department of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts, and became a professor at Musashino Art University in 1998, and is currently vice president and professor at Kobe Design University.

His main publications include “Mashugura no Hana – Nakagawa Yukio” (Bijutsu Shuppansha), “Ishimoto Yasuhiro – Photography as Thought” (Musashino Art University Press), “Arai Junichi – Nuno/Kaleidoscope” (Aesthetic Press), and revised editions of those three books were published as “Miracle Series (2022-23). Other publications include “Design Journalism: Reporting and Conspiracy 1987-2015” (Aesthetics Publishing).

Dates: April 10 (Thursday) – April 30 (Wednesday), 2025

Opening hours: 10:00 – 17:00

Closed: Sunday and Monday

Exhibition Outline